Imagine waking up in a world where technology makes a leap not every year, but every few months. AI writes texts, designs images, and programs faster than you can keep up. For some, this feels like a goldmine; for others, like a storm that swallows everything. The question is not whether that acceleration will continue, but: will you develop along with it, or drop out?

Not everything that moves fast is a hype—sometimes it’s just exponential.

You don’t need to think faster than machines; you need to work with them more intelligently.

We’ve turned this article into a dynamic video presentation — created with Google’s LLM — to bring the key insights to life.

Watch the video below for a concise, engaging overview of The Right Mindset in a World of Exponential Growth and Singularity, or scroll down to read the full in-depth article.

1) Why we underestimate exponential growth

Humans have a persistent exponential growth bias: we read fractions and doublings as if they were straight lines. Recent research shows this directly distorts our estimation of AI progress: participants systematically underestimated how quickly AI capabilities increase.

Our brain loves straight lines; technology does not.

Doublings feel small—until they overtake you.

2) Technostress: the shock of lightning-fast change

Speed itself is a stressor. Recent reviews and studies link the pace of change, uncertainty, and complexity to higher stress and declining performance or well-being. This is not classic technophobia, but an understandable friction between the human pace of adaptation and technological reality.

It’s okay to get tired of ‘faster’—what’s not okay is standing still.

Stress signals: your skills are falling behind your tools.

3) AI and learning: convenience vs. growth

AI can accelerate you—but also unteach you how to think if you outsource everything. In a recent (not yet peer-reviewed) preprint, this is called the comfort-growth paradox: convenience can slow growth. The proposed solution is Enhanced Cognitive Scaffolding: AI as scaffolding that is gradually removed so you take over the work. Experimental educational research with GenAI scaffolds also shows that thoughtful guidance can improve learning outcomes; conversely, over-reliance can create “cognitive debt.” Treat this as preliminary but promising.

Use AI as a springboard, not as a crutch.

Let the assistant help—and then let go.

4) Mindset skills that keep you agile

- Intellectual humility: acknowledging what you (still) don’t know is associated with better judgment and more constructive behavior in conflicts.

- Growth mindset: useful as an attitude, but effects on performance are on average small and context-dependent—don’t oversell it.

- Bias awareness (in humans and AI): large language models show human-like biases (e.g., overconfidence) in a range of tests; keep this in mind.

Humility accelerates learning.

Optimism is good; overestimation is not.

5a) Where people stand now (without artificial boxes)

Instead of hard “three groups” with percentages, recent datasets show this:

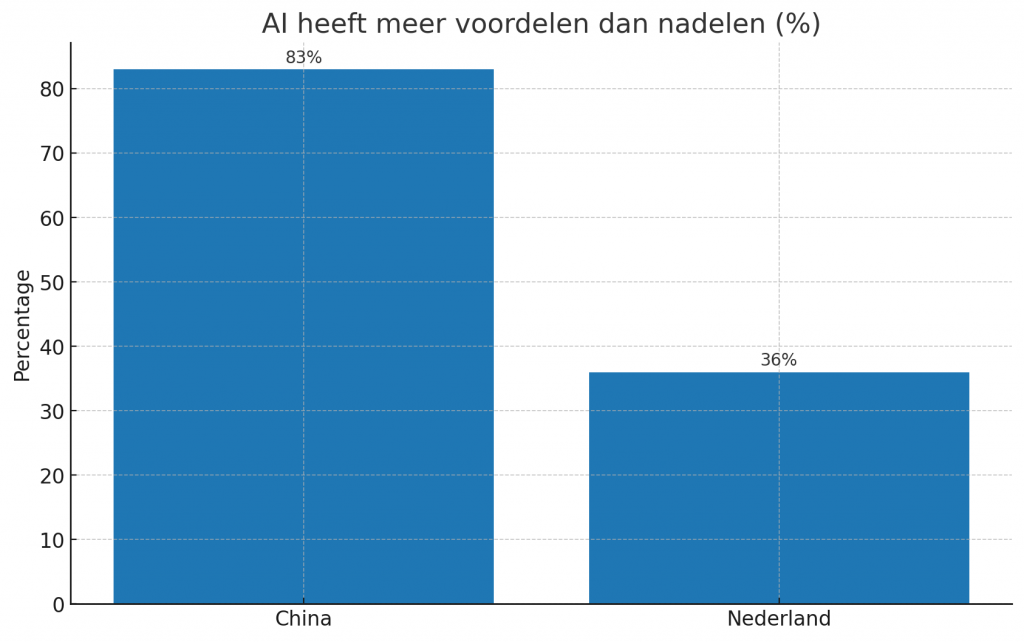

- Globally, the feeling that AI offers more benefits than drawbacks is growing, but country differences are large: e.g., China ~83% ‘more benefits’, Netherlands ~36%.

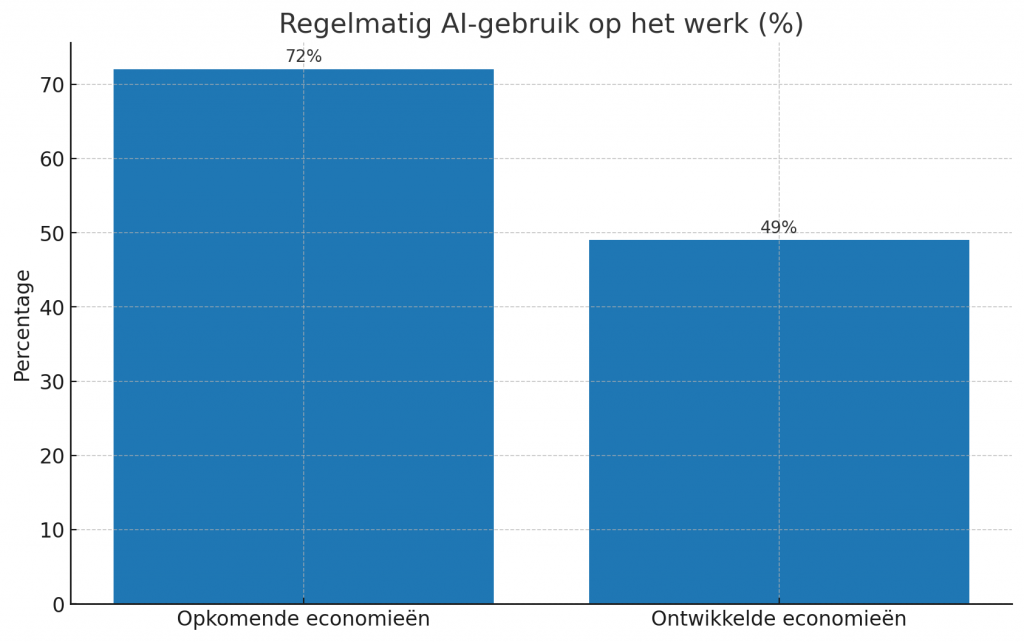

- Adoption and trust are on average higher in emerging economies. At work, 72% in emerging economies use AI at least semi-regularly, vs. 49% in developed economies; organizational adoption is also higher there.

Practically, you could roughly see the public as: early adopters (high adoption/trust), cautious experimenters, and wait-and-see/worried—but the ratio varies by sector and country.

The landscape is not a 3-slice pie: it’s a map with regions.

Where you work and live colors your AI attitude.

5b) Three groups in society (indicative classification, Aug 2025)

Suppose we wanted to roughly divide the world’s population by AI attitude into three groups, we would arrive at the following indicative ranges. This is a thinking framework based on synthesis of recent datasets and trends; these are not official measured shares.

| Group | Description | Global estimate (indicative) |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 – Stamp-sized awareness | Stuck in routines, thinks linearly, sees AI mainly as a threat. | 55–65% |

| Group 2 – Potential growth group | Curious, sees opportunities, learns actively, uses AI as a lever. | 25–35% |

| Group 3 – Transition group | A mix of curiosity and doubt; open to learning but partly clinging to old patterns. | 10–15% |

Note: this classification is hypothetical and intended as a pragmatic framework for policy, communication, and training. Regional/sectoral differences may deviate substantially.

6) Three concrete takeaways

- Train your eye for exponential

Practice with doubling times, S-curves, and order-of-magnitude thinking. This helps reduce the exponential growth bias and improve your planning. - Use AI as a learning partner (scaffold)

Ask for hints, checklists, counterpoints, and a fade-out of help. Keep the bar high enough so you remain cognitively engaged. - Be critical and humble

Calibrate for bias (in human & model), do spot-checks, and maintain your own grip on sources.

Ask for explanation, not just for outcome.

Doubt is not a brake: it’s your steering wheel.

Conclusion

The world is accelerating. Those who combine an open, learning attitude with conscious scaffolding and bias vigilance will not only keep up—but help steer.

Mindset is not a shield against change; it’s your surfboard.

Sources (selection, recent & relevant)

- AI perceptions worldwide — Stanford HAI: AI Index 2025 · Public Opinion (PDF).

- Adoption & trust per economy — University of Melbourne & KPMG: Global Study 2025 (landing) (PDF).

- Exponential growth bias & AI: Meikle (2024), Technology, Mind, and Behavior + KU summary.

- Technostress (speed/complexity): Comprehensive review (2024); AI & technostress (2025).

- AI bias (human-like distortions): Chen et al. (2025), M&SOM.

- Scaffolding with GenAI (education): Computers & Education RCT (2025); Meta-analysis HSS Comm. (2025).

- Comfort-growth paradox (preliminary): Riva (2025) · Enhanced Cognitive Scaffolding (preprint).

- Growth mindset — effect sizes: Sisk et al. (2018) meta-analysis; Macnamara & Burgoyne (2022) meta-analysis.